SITUATING BANKIM IN TODAY’S BENGAL

- By : Anirban Ganguly

- Category : Articles

The Congress, Communists and the lone intellectual in the Trinamool in the midst of lumpens, Sugata Bose, took umbrage that Amit Shah had dared to come to Kolkata and to speak on Bankim

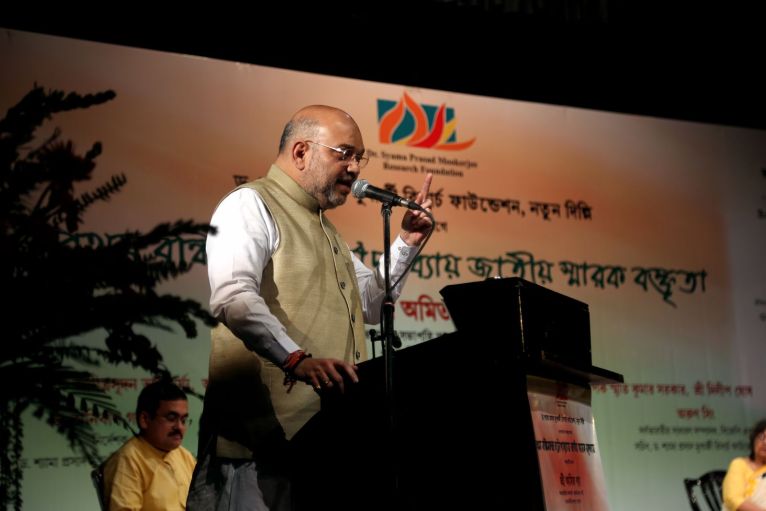

BJP president Amit Shah delivered the first Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay Memorial Oration, instituted by the Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, in Kolkata on June 27. 2018 being the 180th birth anniversary year of the Rishi — the Sage, who as Sri Aurobindo wrote in his opuscule on Bankim, ‘was a seer and nation-builder’, the programme took on a symbolic dimension. Those who came to listen to Shah did so from across the State. It was not a Kolkata-centric event with a metro audience. Young academics and intellectuals from across West Bengal, from district colleges and educational institutions and from State universities had congregated to listen to Shah speak on Bankim and Vande Mataram —his immortal ode to Bharat Mata.

A large number of leading intellectuals and educationists had also come to listen to Shah and share the stage with him; notable among them was Bankim’s foremost Bengali biographer Amitrasudan Bhattacharya and the legendary modern Bengali writer Buddhadeb Guha.

Despite various roadblocks created by elements within the administrative and political establishment of the State, people thronged the venue and the programme succeeded in generating discussion for weeks after the event. Displaying stark opportunism, just two days before Shah’s address, the Mamata Banerjee administration announced a three-day Bankim Chandra festival — a first in seven decades of West Bengal’s existence as a State, while a day after the Oration, the State Government announced it was instituting a Chair in the name of Bankim at the University of Calcutta — again for the first time in seven decades.

In fact, the only time that Mamata Banerjee garlanded Bankim’s photo was just after she had taken over as Chief Minister in 2011. Since then, until 2018, she had desisted from alluding to his contribution and had refrained from even garlanding his portrait. Yet, her party and few of her appendage intellectuals project her as the leader of Bengalis and the party as a party of Bengalis and of Bengal and pay obeisance to her as the ‘premier’ of Bengal! In all this feigned Bengaliness, somehow Bankim went missing and was plastered over due to the false demands and exigencies of the politics of appeasement.

The Congress that ruled West Bengal for three decades after Independence did not think of paying tribute to Bankim through erecting appropriate institutions or memorials recognising his contribution.

During the Marxist phase, Bankim was relegated to the margins, projected as a communal thinker whose words and call for India’s liberation needed to be decimated or at least diluted from the public and intellectual discourse of the State.The Communists and their intellectuals, whose political fountainhead Muzaffar Ahmed (Kaka babu), displaying shallow intellectualism, found Bankim’s Anandamath ‘full of communal hatred from the beginning to the end’ began generating a narrative that Left-leaning intellectuals had refused to attend to Shah’s speech despite being invited.

The likes of Manoj Mitra, Bibhas Chakraborty, Rudraprasad Sengupta, Chandan Sen — all so-called pillars of the Left intellectual movement in Bengal — posed as if they were invited but refused the invitation to Shah’s event! On the contrary, these intellectuals were never reached out to and were not invited to the programme. In their desperation to appear relevant in the mainstream of intellectual discourse, they pretended to have rejected an invite that they had never received in the first place.

The Congress, Communists and a lone intellectual in the Trinamool Congress — an intellectual in the midst of lumpens — Sugata Bose, had actually taken umbrage at the fact that Shah had dared to come to Kolkata and to speak on Bankim, a figure that they have tried, for decades, to marginalise and to eradicate from the Bengali psyche. They behaved as if Bankim was their personal property over whose life and legacy they had sole control and authority over.

Ironically, it was this same Congress party in the opposition in Bengal in 1983, which had moved a resolution in the State Assembly demanding that the government ‘adopt measures to propagate the novel Anandamath’. The greater irony was that the ruling Left Front refused to vote against the motion, while cries of Vande Mataram rent the Assembly. It is a history that the Congress of today would like to forget, because it is a Congress that has become increasingly de-nationalised, de-ideologised and de-linked from the ethos of India.

The inquisitiveness among the people at large was very encouraging; first, they wanted to hear Amit Shah who was speaking on a topic which was not the usual political-type subject and secondly because the oration was on Bankim. It was perhaps for the first time that Bankim Chandra’s birth anniversary was being observed through such a grand programme in the city. The programme was not a political programme; the venue, the famed GD Birla Sabhaghar was not a political forum; and the topic was an ideational, ideological and cultural issue aimed at the psyche and soul of Bengal. Shah that evening spoke from the heart, he referred to Bankim as the father of modern cultural nationalism, spoke of how Bengal through Chaitanya Mahabprabhu, Sri Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, Bankim and Sri Aurobindo had been the fountain of cultural nationalism and how that heritage, that past, needed to be revisited.

Shah spoke of India as a geo-cultural rather than a geo-political entity and argued that it was Bankim who, describing India as the Mother, had put his seal on this vision of Bharat as a geo-cultural and spiritual entity.

The discourse had been taken to an altogether new level in which the political was subsumed to the inspirational, ideational and philosophical dimension. His most poignant and hard-hitting point was that the fragmentation of Vande Mataram in 1937, with Congress’s hesitation in singing it in its entirety, paved the way for the fragmentation of the country. That act of omission announced the era of appeasement politics, which eventually led to the Partition of India. It was an act of sacrilege, which tampered with the sacred spirit and dimension of India and her spiritual and cultural unity. These observations have struck a deep chord in the Bengali psyche, the Bengalis being a people most affected by the charade of the politics of appeasement. That act of fragmentation remains forever condemnable. Shah reminded us of that.