The foundation of a new political narrative

- By : Anirban Ganguly

- Category : Articles

It is symbolic and significant that the seventieth anniversary of the first general election and the seventieth year of the founding of Bharatiya Jana Sangh, predecessor of Bharatiya Janata Party, are being observed this year.

The Jana Sangh’s first biographer, Craig Baxter, spoke of the party as having, “a unique position among the national political parties of India”; it was the only political party in India, that had”‘increased its percentage of the popular vote and its share of parliamentary and assembly seats in each successive election from 1952 through 1967.”

The Jana Sangh had another distinction; it was the only national party to be formed within five years of independence by a Bengali ‘bhadralok’ , Syama Prasad Mookerjee, from south Kolkata, who was determined to set the course by evolving an alternate political narrative and structure to the dominant Nehruvian Congress.

The founder of the Jana Sangh and his young political co-workers were clear that the new political formation was not founded merely keeping the impending election in mind, nor was it formed simply to oppose the Congress. They were convinced that they were laying the foundations of a new political narrative for independent India which would articulate, symbolise and embody the aspirations of an independent India.

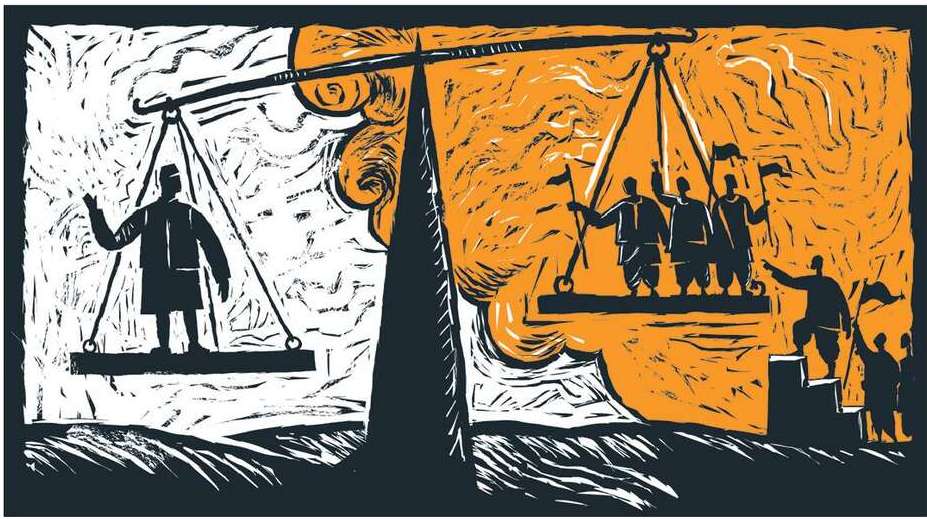

Deendayal Upadhyaya, Mookerjee’s lieutenant and understudy perhaps best described the raison d’etre of Jana Sangh on the eve of the general election. The Jana Sangh, Upadhyaya pointed out, did not have a nucleus formed of “disgruntled, dissident or discredited group of Congressmen” as was the case with other political parties that were being formed. The Jana Sangh’s inspiration, “came from those who basically differed from the Congress outlook and policies.”

Writing in the midst of elections in January 1952, on “Congress versus Jana Sangh”, Upadhyaya pointed out that the “dilemma before the purposeless Congress and its workers, after independence” was “to identify a task” to which they could commit themselves. He likened the Congress to a corpse which was decaying, “with parts falling off every now and then.” Out of this decaying mass, Upadhyaya caustically wrote, “have sprung up other organisms we know as different political parties, the socialists being the first.” But these parties, he argued, were created “merely for the sake of opposition” and had no “real basis of their own.” The Jana Sangh was completely different, he said: “We have to seek a fundamental basis in order to solve our problems. We have to look ahead, and not merely stand in opposition.” Jana Sangh, in Upadhyaya’s words, did “not exist merely to oppose the Congress. The task of making the country happy and prosperous [was] foremost in its view.” These were the cardinal and fundamental differences between the newly formed Jana Sangh and the other splinters of the Congress which had joined the fray of the general election.

When Syama Prasad Mookerjee launched the Jana Sangh on October 21, 1951, multiple challenges faced the fledgling party. Its first task, besides putting together a national and provincial organisation, was to prepare for the general election and all that it entailed – candidate selection, fund raising, manifesto, campaign plan and much more. The first general election was just two months away, candidates who would fight the elections under Jana Sangh’s symbol, Deepak, were hard to find. Jawaharlal Nehru had publicly vowed to “crush” the Jana Sangh, to which Mookerjee had famously retorted that he would crush his crushing mentality and above all the incredulity with which people in general looked at the attempt. The workers, though trained and motivated, lacked political experience and, as one early participant pointed out, “its very name was unknown to an overwhelming majority of people.” The Jana Sangh members dubbed Nehru as the party’s “honorary publicity secretary” since, the Prime Minister, in nearly every meeting was raucously vituperative against their party, thereby making it clear that the new party was the Congress’s principal and most serious adversary.

Despite great odds, a huge resource crunch, lack of infrastructure and a support system and fronts as compared to the Congress behemoth, the Jana Sangh, succeeded in winning three seats, with Mookerjee himself winning the south Kolkata Lok Sabha seat. As K.R.Malkani, wrote, “although the new party did not win too many seats, it secured more than 3% [3.06] of the popular vote and thus qualified as one of the five recognised national parties.” Mookerjee told the Jana Sangh workers after the results: “We began with zero and we have now got something plus everywhere. We have gained something and lost nothing.”

It was the start of a seven decade long relentless journey which ensured that seven decades after he founded the Jana Sangh, seven decades after the first general elections, and 75 years after India became independent, Mookerjee’s party, in a new avatar, would dominate India’s political firmament.