Towards Swarajya

- By : Anirban Ganguly

- Category : Articles

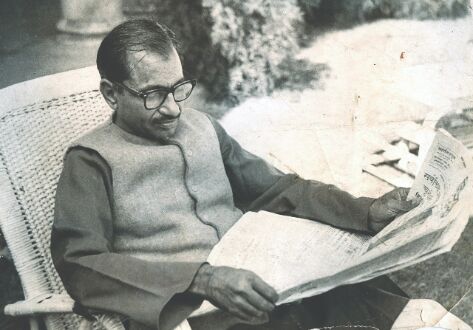

Remembering the many lessons of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya — on the occasion of his birth anniversary — regarding the preservation of India’s self-esteem and identity

Besides being a quintessential organisational leader, Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya’s persona had another outstanding dimension to it. Not only was he a profound political philosopher, but he also displayed a very compelling capacity of envisaging, articulating and expressing that philosophy in the field of pragmatic politics as well.

An indefatigable political commentator and observer, Upadhyaya wrote prolifically. His impulse to impart political direction and inspiration drove him to constantly comment on our national evolution, and on the path that India was being driven to take, on the contemporary challenges to our national regeneration and especially on the future direction that she ought to follow for her fullest self-expression. It is an interesting and elevating exercise to follow the evolution and flow of Deendayal Upadhyaya’s mind, his thoughts, his political positions and inspiring formulations, made at a time, when the Nehruvian behemoth was dominating, when the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, of which he became the front-ranking general secretary, was struggling — albeit determinedly — to gain a foothold in national politics, when the atmosphere, among the cadres of the party, due to electoral defeats and seemingly insurmountable challenges before them, was despondent.

One comes across a very apt description of the Nehruvian state in Tripurdaman Singh’s ‘Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India’. The Nehruvian state had an ‘odious state apparatus’, a ‘prescriptive dominance of a personality-driven social agenda, its overwhelming primacy of executive authority, and its grim, resolute suppression of alternative ideological positions — all precariously balanced against a pedantic dedication to the democratic procedure and collective policymaking.’ It was this hegemony that Deendayal Upadhyaya and the Jana Sangh relentlessly challenged

To be able to maintain a sustained, relentless, steady and unflagging effort in trying to create a counter political narrative to such a behemoth, to make an effective alternate political movement and platform against such an imposing hegemony of the Nehruvian structure, demanded more than political zeal, it demanded a determined and fundamental belief in the ultimate triumph of the vision of politics that was being expressed and worked out in opposition to the Congress.

Deendayal Upadhyaya radiated that fundamental faith. He was also quick to remind the workers and enthusiasts of the fledgeling Jana Sangh, that the party was formed not merely to oppose the Congress, in fact, he never failed to reiterate that its first and foremost raison d’être was to espouse and put forth a different vision of India, an indigenous vision, rooted to and would evolve from the Indian ethos. The ‘Jana Sangh’, he wrote in January 1952 around the time when the first general elections were being held, ‘does not exist merely to oppose the Congress. The task of making the country happy and prosperous is foremost in its view…The rise of the Jana Sangh has come about to dispel this environment of gloom and rekindle hope and energy in the country…’

The Jana Sangh presents, he argued in his first address as the ‘Pradeshik Mahamantri’ (State General Secretary) of Uttar Pradesh, “the fundamental principles of our nation’s way of life. The Jana Sangh believes in the principle of one nation, one people and one culture.” This was the basis on which it strives to build and develop the nation.”

A look at his writings and speeches, of over nearly three decades, from the 1940s to his sudden death in 1968, offers an interesting perspective in the world of Upadhyaya’s political mind. Besides being inspirational, they retain a capacity to infuse an ideological reiteration and orientation, in short, they inspire and root the reader.

A short, lucid and inspiring address of his, perhaps his last as Sah Prant Pracharak of RSS, before joining Jana Sangh, on the ‘Resolve to Fulfil Shivaji’s Dream’, delivered on the anniversary of the coronation of one of the most iconic figures in Indian history, contains some very relevant points. Upadhyaya spoke of the need for “indomitable will to succeed in one’s task. One can’t worry about what others say.” Much like Shivaji who displayed such a will, who did not care what others had to say about him. This confidence, Upadhyaya pointed out, enabled Shivaji to establish an “empire of Dharma, which protected the pious and safeguarded the wealth of our country.” Shivaji ruled for the sake of two attributes, “Swadharma and Swarajya”. To fulfil his dream would be to re-establish ‘Swarajya’ and ‘Swadharma’.

In this address, as early as 1951, Deendayal Upadhyaya cautions against adopting and promoting skewed secularism, “the slogan of a secular state is being raised with great fanfare”, he told his young audience, “but secularism cannot mean the contempt for national traditions and the cultural life of a nation. Secularism that is based only on materialism can never match the nature and way of life of the people of our nation.”

The decades that followed proved Upadhyaya prophetic. The Nehruvian establishment propped itself upon a consensus that would promote secularism which was antithetical to and hostile towards our traditions and faith. It would actively seek to suppress and marginalise these and would profess a disdain and contempt for them. This warning of Upadhyaya was, in effect, a warning against adapting pseudo-secularism as the underlying thought of the Indian State. That pseudo-formulation of false secularism has now begun to be challenged and exposed.

In a lot of what he wrote and articulated, Upadhyaya argued for the need to realise and internalise the deeper unity of our collective-self. The sources and centres of our inspirations, he argued must “always be within.” In a sense, if the principle of national freedom, as Yoram Hazony, a leading Jewish political thinker has argued, ‘offers a nation with cohesiveness and strength to maintain independence and self-government, and to withstand the siren songs of empire and anarchy, an opportunity to live according to its interest and aspirations’. Deendayal Upadhyaya, since the early years of India’s independence, insisted on it. The Jana Sangh’s political line and philosophy of one nation, one culture, attempted to give shape to this argument of the need to crystallise the sense and feel of the nation in our collective psyche. As JH Herder argued in his ‘Ideas on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind’, ‘the most natural state is…one nation, an extended family with one national character.’

The “talk of one nation and one culture may seem to some ‘woolly-headed nonsense’, observed Upadhyaya, “but it is a fact nevertheless. Those who have borrowed all their ideas and theories from the West may find it difficult to understand and appreciate the inherent unity of our nation. Some divisive political demands might be misconstrued to represent a lack of nationality. But the facts of our culture, traditions, customs, history, philosophy, art and literature are so abounding and powerful that none but the obstinately purblind can refuse to recognise the existence of a single indivisible nation.”

The identification of one’s own national interest and aspirations and the need for pursuing these while disseminating the sense of one national character was embedded in Upadhyaya’s political-philosophical formulations. It was, therefore, necessary to keep the “nation’s identity alive,” he argued, “so much so that even if we have to acquire something from outside, we do so in a way that it should become our own…”

With the consciousness of a national character, must rise the sense of “self-esteem”, a “feeling of the heart” which is essential for the “development of the individual and the nation.” This rekindling and preservation of “self-esteem”, must necessarily lead to the quest for “self-reliance”, and the fountain source, the inspirational foundations for self-reliance, must be within, “every nation, has to think about its centres and sources of inspiration, which must always be within”, Upadhyaya argued. It is an interesting characteristic of his vast corpus of writings that one finds a lot of it self-renewing. It is in that light that one ought to read and reinterpret Deendayal Upadhyaya and the contours of his ideational world. Unlike the corpus produced by calcified Marxist thinkers of his era, a lot of Upadhyaya’s thoughts and articulations — rooted in the organic civilisational fabric of India — continues to be both perennial and contemporary.