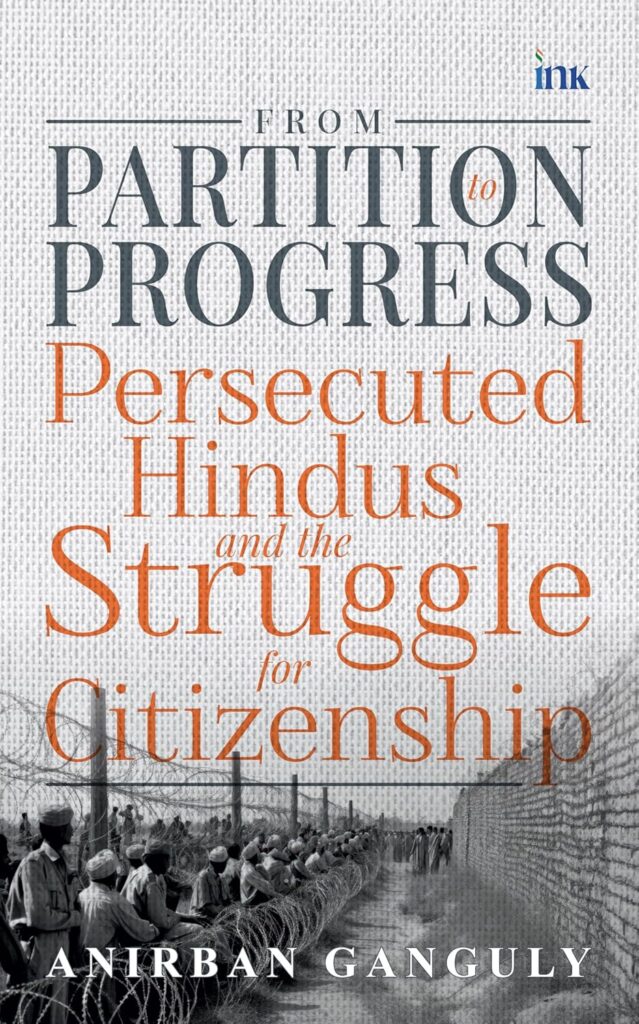

SUCCESS STORIES OF ANCIENT INDIA

- By : Anirban Ganguly

- Category : Articles

It is good that the political discourse has at last gradually begun to move us nearer to our true and essential political and cultural self

On a visit to southern India last week, I crossed the small town of Utthiramerur in the district of Kancheepuram in Tamil Nadu. A nondescript signpost indicated the direction to the town. What remained unsaid and uncommemorated, however, was the area’s unique contribution to the evolution of representative institutions in Indian civilisation and its role in evolving standards of conduct and ethics in our public life. More than a thousand years ago, the village of Utthiramerur had evolved an elaborate electoral system and possessed a written Constitution with strict stipulations for the holders of public office.

To the people and nation which has, for quite a while now, sustained its intellectual and historical discourse on theories and frameworks that were predominantly conceived and evolved by the dominant ‘outsider’, these past achievements are rarely referred to or discussed. A large and vocal section in the Indian academia today prefer to brush these aside as inanities because these past civilisational achievement do not conform to their theory which advocates, ad nauseam, that nothing good, noble or original ever came out of Hindu civilisation.

The standards and injunctions enunciated, through a collective effort, by the leaders of the Utthiramerur village during the peak of the mighty Hindu empire of the Cholas, remains vibrant in a contemporaneous light, especially in the current political climate. To look at some of it in the midst of the present democratic churning gives an insight into how nepotism and dynastism were never acceptable in Indian democracy — or at least the indigenous version of it evolved through millennia in course of our civilisational march.

In his monograph, Elections in Ancient Tamilnad, R Nagaswamy, one of the leading Indian epigraphists discusses these fascinating electoral cannons of Indian civilization. He points out that the Utthiramerur inscriptions of 920 CE were meticulous and severe and strove to uphold high standards in public life and conduct. The inscriptions insisted on fixing a certain minimum and maximum age limit for those aspiring for office. It did not support the urge among candidates to perpetuate themselves in power beyond the stipulated age limit. It pointed out that such an urge “would create a sense of frustration in the younger generation and there would be no smooth or gradual change over.”

Among other issues the Utthiramerur electoral framework insisted that a “candidate ought to be an honest man” who had “acquired his property through honest means and not one who took shelter under legal intricacies and appeared honest”. It also preferred candidates who were known for or had proven “administrative ability (Kaaryattil nipunar)” and the novice, the confused and the braggart were usually discouraged from contesting.

The Utthiramerur inscriptions’ stipulations for disqualification of candidates were severe. It enumerated the following sins for disqualification: “One who was guilty of neglecting proper accounting at the end of the year” despite having been elected to one of the public committees was to be “disqualified from standing for elections throughout his life”; “Any elected member who accepted bribe was also permanently debarred from standing for elections”, “One who misappropriated any property was also disqualified” as was one who “acted against the interest of the society and was a potential danger to the peaceful life of the people and was seen as a graama kantaka” (village thorn). Interestingly not only was the individual guilty of any of the above faults disqualified from seeking election but also “all his relations in the father’s family, the mother’s family and his wife’s family were permanently debarred”.

The last six decades of our politics has only served to eradicate the memory of the Utthiramerur injunctions — it is a sign of hope that the political discourse is now altering and has at last gradually begun moving us nearer to our true and essential political self.